I love to collect possible titles for pieces I’ll probably never write. (It’s my version of “Hey, that would make a good name for a band.”) There are many scientific concepts that would make great titles, and some that perhaps sound more like a book title than like what they really are. Here are a few examples:

The Sphere of Confusion This quantity describes the accuracy of a goniometer, which is used to measure angles, but wouldn’t it make a good title for a domestic thriller about someone who’s gaslighting another person? Or maybe a novel about war. This one has a lot of possibilities, life being as confusing as it is.

The Equation of Time This describes the difference between two types of solar time, that is, time based on where the sun is in the sky. For some reason this sounds to me like a good title for a memoir, or maybe a multigenerational family saga. It might also work as a title for a nonfiction book on the mathematical modeling of history (e.g., cliodynamics).

The Cosmic Censorship Hypothesis This is a mathematical statement regarding the invisibility of singularities in general relativity, but it would also make a great science fiction title.

The Three-Body Problem This is the problem of describing the motions of three bodies that interact under Newton’s laws and the law of gravitation, given their initial positions, velocities, and masses. It would also make a nice title for a story about a relationship triangle, particularly a romantic triangle.

The Law of Tolerance In ecology, this law describes the way that the distribution or abundance of a species is determined by a certain limiting environmental factor or combination of factors. But it might make a good title for a geopolitical thriller, or, going to the other extreme, a cozy novel about small-town life.

The Principle of Least Action In physics, this principle provides a way of describing the motion of objects that is independent of Newton’s laws. But it sounds poetic enough that it would be a great title in any number of contexts. I can imagine a novel about a person who slides through life without attempting much, or perhaps a book about a Zen community.

The Islets of Langerhans These are areas in the pancreas where hormone-producing cells are found, but I could believe this is the title of a novel about an idyllic summer in a fictional Baltic location.

The Crypts of Lieberkühn These are glands found in the lining of the intestines, but the phrase certainly sounds like the title of a Victorian Gothic novel to me.

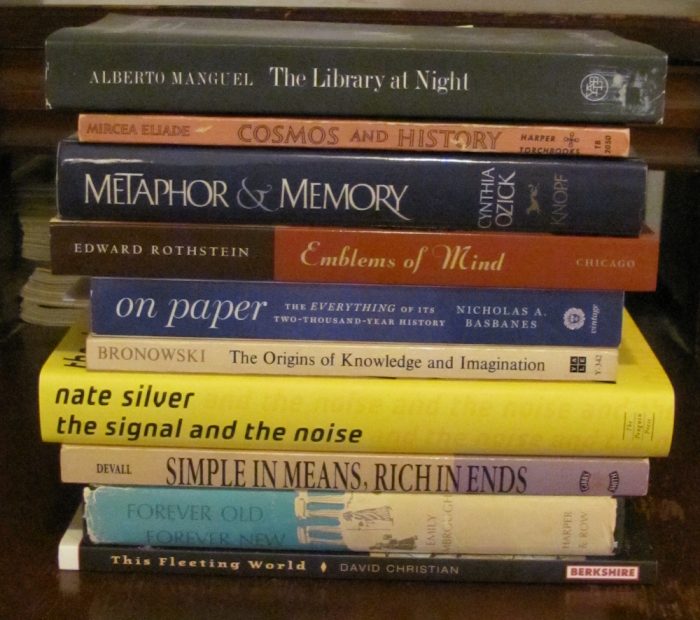

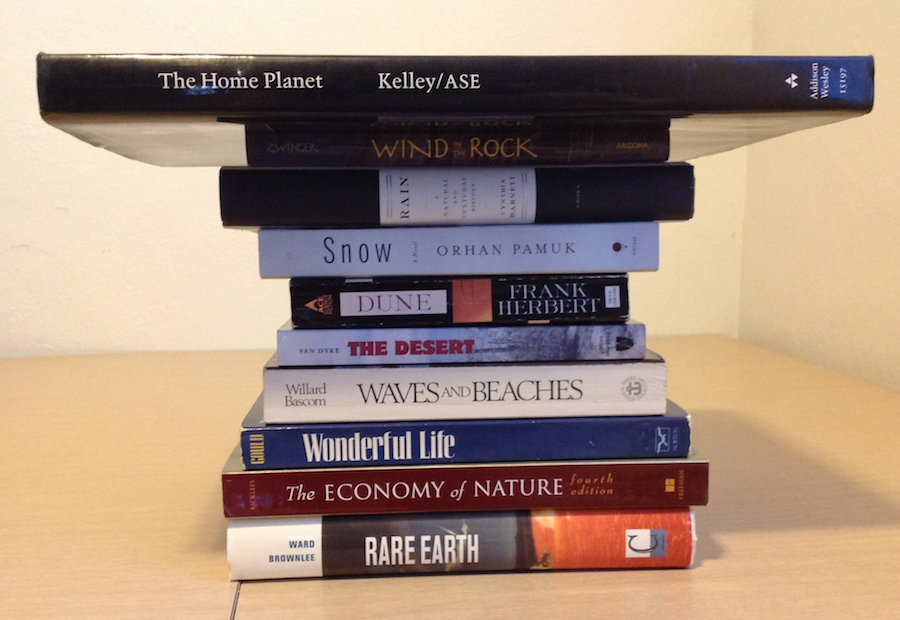

Obviously I’m not the first to have thought of borrowing titles from science. Wallace Stegner called one of his novels Angle of Repose, after a term used in geology to describe the largest angle at which a slope consisting of loose material can remain stable. Similarly, Shirley Hazzard wrote a novel called The Transit of Venus, after the relatively rare astronomical event in which we see Venus passing directly in front of the sun. I’m sure there are many other possibilities; post your ideas in the comments.